January 2026 LIP of the Month

Volcano-sedimentary response to a mantle plume decay at the Eastern Mediterranean margin

A. Segev a and U. Schattner b

aGeological Survey of Israel, 32 Y. Leibovitz Street, Jerusalem 9692100, Israel. amitsegev0@gmail.com

bSchool of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Haifa, Israel.schattner@univ.haifa.ac.il

Extracted and modified from:

Segev, A., Sass, E., Schattner, U., 2025. Volcano-sedimentary response to a mantle plume decay: A case study from the Eastern Mediterranean margin. Geoscience Frontiers, p.102161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2025.102161

Abstract

The decay of a mantle plume is characterized by a decline in magmatic activity, localized volcanic pulses, and short-term topographic fluctuations. These processes are better preserved in marine settings than on land, offering a clearer record of surface dynamics. This study examines the decay of the Levant mantle plume during the Albian-Cenomanian by analyzing the effects of recurring volcanism and vertical motions on the volcano-sedimentary stratigraphy exposed at Mt. Carmel on the eastern Mediterranean continental margin. Geological mapping and 40Ar/39Ar dating reveal four distinct volcanic pulses (V1–V4) between ~99 Ma and 95.4 Ma, each associated with surface uplift followed by subsidence and sedimentation. These cycles suggest pressure accumulation and release, likely driven by residual plume-related magmatic activity rather than regional tectonics. Volcanism, vertical motions, and shallow marine areas created local basins with varying connections to the sea, resulting in diverse depositional environments characterized by lithologies such as chalk, limestone, dolomite, marl, and tuff. The volcanic structures influenced facies changes and contributed to dolomite formation in shallow, partially closed marine environments. A final pulse, V5 at 82 Ma, occurred after 13 Myr of quiescence, marking a shift in the regional tectonic setting. The lack of post-Maastrichtian volcanism and a 25 Myr long period of subsidence indicate plume termination. These findings demonstrate how a decaying plume loses its ability to influence surface dynamics. The Albian-Turonian reefs, situated atop a long-lasting crustal high at the Arabian platform’s edge, serve as a significant example for analogous worldwide.

1. Introduction

The rise of a mantle plume induces regional lithospheric uplift (doming), thermal expansion, volcanism, faulting (rifting), and erosion of the Earth’s surface (Courtillot and Renne, 2003). At their peak, uplifted areas span hundreds of kilometers in concentric or complex geometries (Ribe and Christensen, 1994). Plume surfacing exhibits periodicity, with a ~14 Myr cycles during early magmatic stages and ~60 Myr during peak plume activity (Prokoph et al., 2013; Rampino and Prokoph, 2013). As the plume decays over millions of years, heating and volcanism become localized and pulsative, driven by residual thermal anomalies and lithospheric thinning (Sleep and Windley, 1982; Jerram and Widdowson, 2005; Orellana-Rovirosa and Richards, 2018). This leads to short-term topographic fluctuations and localized volcanic activity, which ceases with plume termination (Clift, 2005; Saunders et al., 2007). During post-cooling, magmatic material accumulating beneath and within the crust imposes an additional load on the subsiding lithosphere. The frequency and duration of pulses remain poorly constrained, influenced by lithospheric thickness, plume buoyancy flux, and regional tectonics (Orellana-Rovirosa and Richards, 2018).

Volcano-stratigraphic variations provide a robust proxy for reconstructing short-term topographic fluctuations and plume pulsations. In continental regions, erosion and drainage systems often obscure these records (Clift, 2005). The marine environment at continental margins preserves such signals through cyclic uplift-subsidence transitions that enable sediment accumulation and stratigraphic preservation (Saunders et al., 2007). The volcano-sedimentary record helps reconstruct local sea-level changes, reflecting the thermal doming-to-subsidence cycle typical of plume-lithosphere interactions, influencing surface topography through phases of plume impingement, domal uplift, thermal buoyancy, regional emergence, erosional unconformities, thermal decay, subsidence, and marine transgression (Watts and Zhong, 2000). When combined with volcanic events and lateral facies changes, volcano-stratigraphy provides a precise tool for tracking plume-induced relative sea-level variations, depositional environments, event timing, and regional tectono-magmatic regimes.

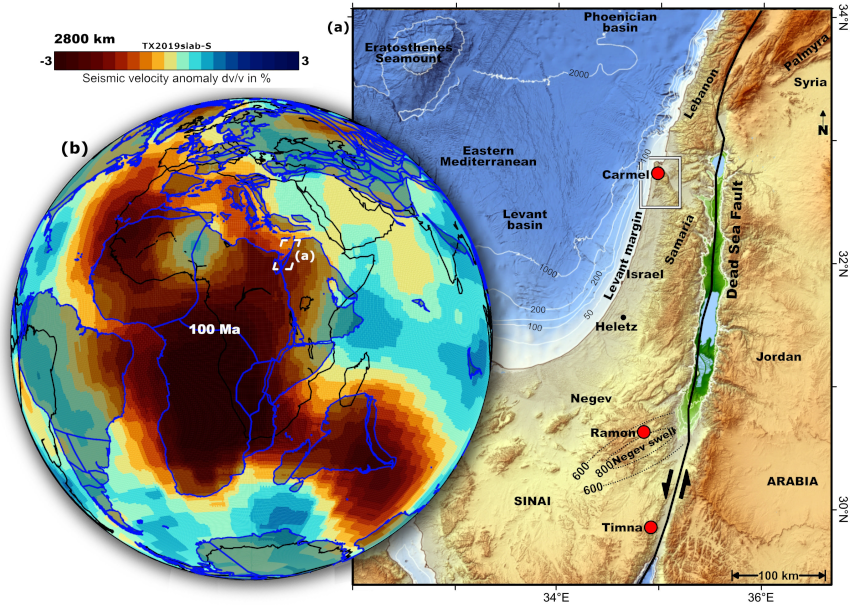

This study examines the effect of a decaying plume on Earth’s surface, reflected in fluctuating continental margins. It explores transitions between subaerial and marine conditions and evaluates uplifts and subsidence during plume decay, focusing on the Levant margin (eastern Mediterranean; Figs. 1, 2), situated above the Large Low-Shear Velocity Province (LLSVP) linked to mantle plume generation (Fig. 2b; Torsvik et al., 2010; Koppers et al., 2021). Over >250 Myr, the Levant endured four mantle plume episodes that heated, uplifted, and rifted the lithosphere. In this context, we concentrate on the extensively studied Carmel area at the center of the eastern Mediterranean continental margin. Although its surface geology has been thoroughly analyzed from a plate-tectonic perspective, the influence of mantle plumes remains underexplored.

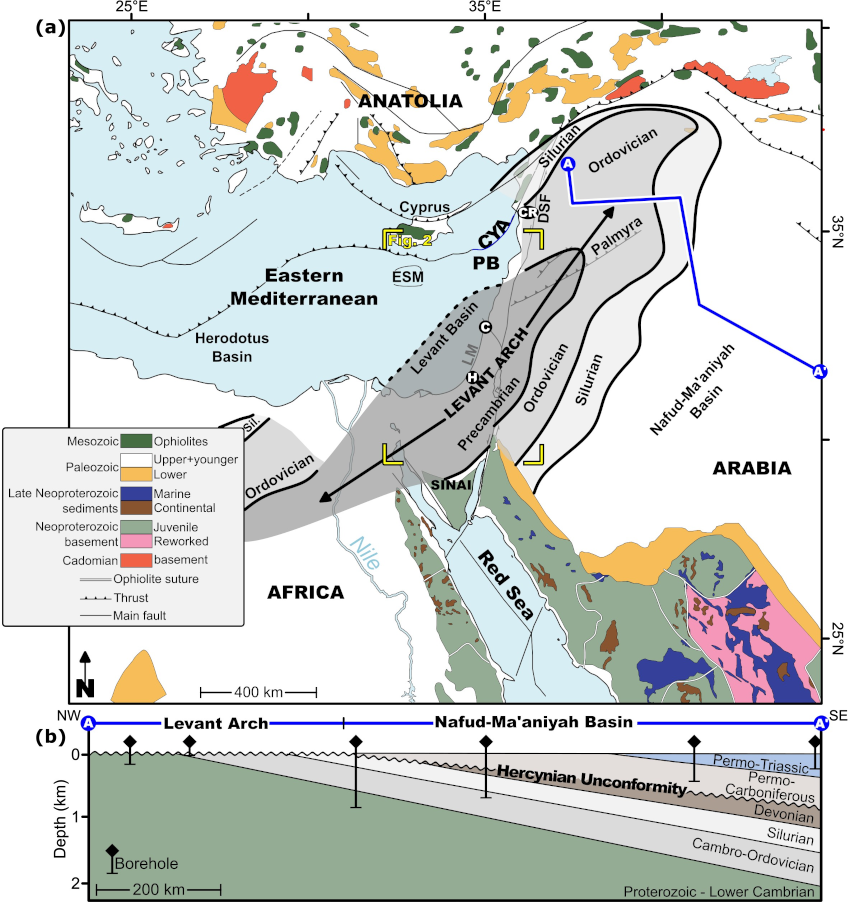

Fig. 1.(a) Regional geological framework of the Middle East with major tectonic boundaries (modified from Bouysse and Ségoufin, 2009; Avigad et al., 2016). Cadomian- and Avalonian-type basement appear in northern areas, from Iran through Turkey to Crete and southern Italy (references in the text). Levant Arch is marked after Wood (2015). ESM-Eratosthenes Seamount, H-Helez deep borehole, C-Carmel, LM-Levant margin, DSF-Dead Sea Fault, CR-Syrian Coastal Range, CYA-Cyprus Arc, PB-Phoenician Basin. (b) Schematic cross-section between boreholes in the northern Levant arch, showing the regional truncation of the Hercynian unconformity (modified after Gvirtzman and Weissbrod, 1984; Best et al., 1993; Aqrawi, 1998; Konert et al., 2001; Mohammad, 2006; Al-Hadidy, 2007; Faqira et al., 2009).

Fig. 2.(a) Location of the study area at the center of the eastern Mediterranean continental margin, between the margins of the Levant and Phoenician basins (relief from EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium, 2025). Seafloor relief in meters below sea level. Red circles – locations of the main magmatic provinces in Israel: Carmel, Ramon, Timna. Negev Swell location and uplift (meters) are marked based on Gvirtzman and Garfunkel (1997) and Gvirtzman et al. (1998). CR-Syrian Coastal Range, CYA-Cyprus Arc. (b) Seismic shear velocity anomalies at the core-mantle boundary, 2800 km, calculated here using the TX2019Slab-S model with the Oxford SubMachine tool (Lu et al., 2019; Hosseini et al., 2020). Colors represent the percentage of seismic velocity anomalies, showing the location of the study area above the Large Low-Shear Velocity Province (LLSVP). Black lines – modern coastline. Blue line and shaded gray areas – location of plate reconstruction for 100 Ma (model by Matthews et al., 2016).

2. Geological background

2.1 Regional development

The Levant basin, in the eastern Mediterranean, developed during the breakup of the Gondwana supercontinent. Its tectonic evolution is closely linked to mantle plume ascents that repeatedly spread beneath the region, fueling intrusions and volcanism, and causing regional uplift, lateral extension, and denudation. During the Late Devonian-Early Carboniferous Hercynian (Variscan) orogeny, Gondwanan terranes collided with Laurasia. In the far-field constructions related to this orogeny, three NNE-trending mega folds formed across the region, later becoming the Arabian Plate (also called arch and geanticline; Gvirtzman and Weissbrod, 1988; Weissbrod, 2005; Faqira et al., 2009; Wood, 2015). The Levant Arch extends roughly between NE Egypt and NW Syria (Fig. 1).

A regional thermo-tectonic event occurred in the Levant during the same timeframe (381–365 Ma). Its extreme crustal thermal gradient (≥50 °C/km; Kohn et al., 1992) is associated with hydrothermal activity (Segev et al., 1995). Vertical movements formed regional-scale swells, hundreds of kilometers long, and intervening basins. Widespread erosion of swell crests formed stratigraphic discontinuities attesting to their non-orogenic origin (Weissbrod, 2005; Faqira et al., 2009; Wood, 2015). After denudation of the Hercynian arch reached below its crest (Wood, 2015), the Syrian NNE-trending Palmyra continental rift developed (also called “trough”). Data show that the rift remains measure ~170 km wide today (Brew et al., 1999, 2001). The rift extends across the Levant margin, where it splits into two branches. The eastern branch extends southward through central Israel, and the western branch underlies the Mediterranean Levant Basin (Brew et al., 1999; Segev and Eshet, 2003). These branches were separated by the elevated Carmel-Heletz high structural block along the current margin (Figs. 1, 2; Segev and Eshet, 2003; Segev et al., 2025).

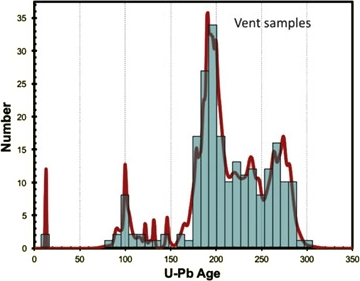

2.2 Paleozoic Gevim Volcanics

The ~200 m thick Gevim Volcanics, consisting of quartz porphyry, overlay basement rocks in Helez Deep-1A borehole with an Rb-Sr age of 275±47 Ma (Segev and Eshet, 2003). In-situ U-Pb zircon ages yield mainly Carboniferous ages of ~351 Ma (Golan et al., 2018), likely representing zircon crystallization in the crustal magmatic system, while Permian dates represent zircon alteration during eruption. The Rb-Sr age thus represents the eruption age. Similar inheritance of older zircons in younger eruptions occurs in tens of U-Pb Permian-Jurassic zircons sampled by Cretaceous Mt Carmel volcanics (Fig. 3; Griffin et al., 2018).

Substantial geological evidence supports these ages. Two boreholes near Helez-Deep 1A (Gevim-1 and Pleshet-1) host a volcanic layer between the Lower and Upper Members of the Permian Sa’ad Formation. Biostratigraphy indicates an early Permian age (~280 Ma), correlative with unpublished 40Ar/39Ar dates from exposed basaltic sills within a Carboniferous clastic succession in southwestern Sinai. They show a wide range of mainly Permian ages of 274±4, 266±4, and 240±4 Ma (Steinitz et al., 1992). A younger ~100 m thick volcanic layer (Heimar Volcanics) within the Late Permian (~255 Ma) Arqov Fm was penetrated by the Heimar-1 well.

Fig. 3. Age histogram and cumulative probability curves for Cretaceous vent zircon samples (80–350 Myr), U-Pb data of Mt Carmel (after Griffin et al., 2018).

2.3 Repeated mantle plume activity

The tectonic evolution of the Levant area is connected with mantle plume ascents spreading beneath the region, fueling intrusions and volcanism while causing regional uplift, lateral extension, rifting, crustal thinning, and denudation (Fig. 2; late Anisian, ~250 Ma; Wilson et al., 1998; Segev, 2000; Derin, 2016; Griffin et al., 2018; Segev et al., 2018). Three plumes significantly influenced the region between the Permian and Late Cretaceous.

The Permian-Triassic plume (ca. 285–240 Ma) formed during and after the Carboniferous Hercynian orogeny, characterized by significant uplift, erosion, increased geothermal gradient, and magmatism (Stern et al., 2014; Golan et al., 2017; Abbo et al., 2018). Its rise and subsequent flattening caused widespread uplift and denudation (~250 Ma; Derin, 2016), magmatism, and rifting along the Palmyra trend from southwest Syria to central Israel (Figs. 1, 2; Brew et al., 1999; Segev and Eshet, 2003).

The Western Tethys mantle plume played a crucial role in the breakup of northern Gondwana and the opening of the Mesotethys Ocean, including the formation of the Herodotus Basin (also known as southern Neotethys; Segev, 2000; Frizon de Lamotte et al., 2011; Guerrera et al., 2021; Criniti et al., 2023, 2024). The plume head expanded southward, initiating magmatic activity at 215 Ma, intensifying between 207–201 Ma, and recurring in the Middle Jurassic (160–170 Ma), as evidenced by the Asher and Devora (Israel) and Bhannes (Lebanon) volcanic formations (Lang and Steinitz, 1990; Griffin et al., 2018; Golan et al., 2021). These processes led to dynamic upwelling, Carmel uplift, crustal stretching, and differential peripheral subsidence (Segev and Eshet, 2003; Korngreen and Benjamini, 2013; Derin, 2016).

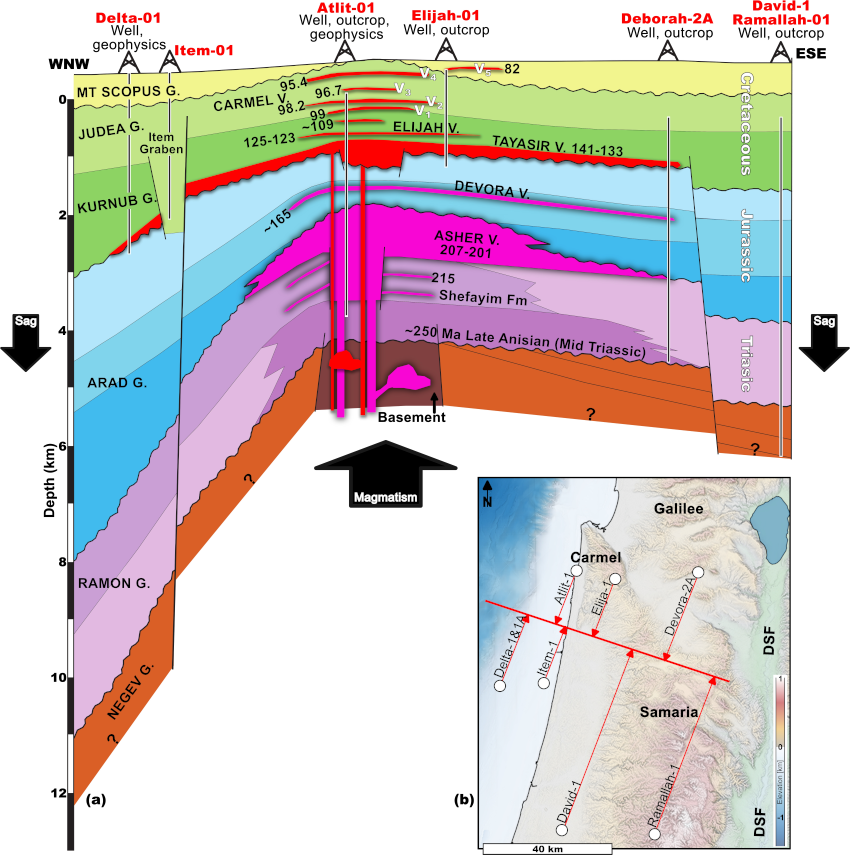

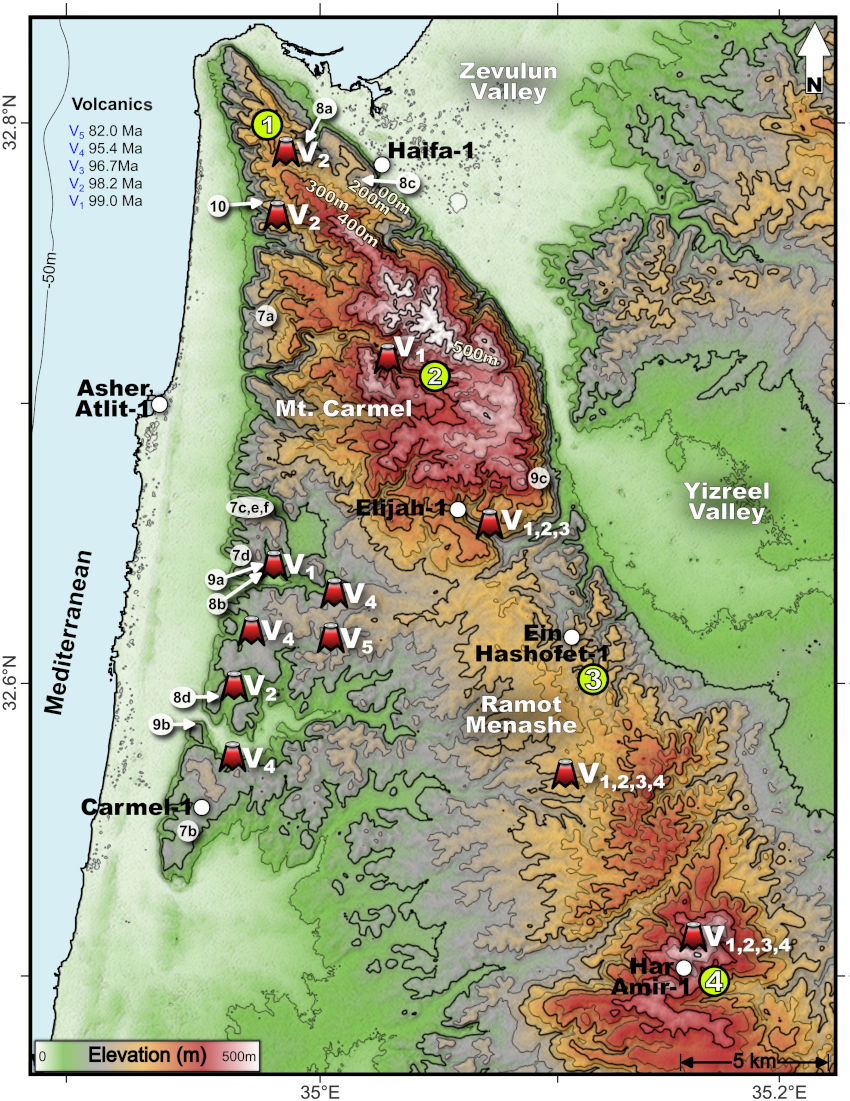

The early to mid-Cretaceous Levant-Nubia mantle plume created an igneous province across eastern Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, and southwestern Syria (Palmyra; Fig. 2). Significant magmatism, uplift, and erosion occurred across the Negev swell of southern Israel (116–108 Ma Ramon magmatism; Gvirtzman et al., 1998) with lesser Carmel uplift. This activity generated the 400 m thick 141–133 Ma Tayasir and 125–123 Ma Elija volcanics, associated with uplift, erosion, plutonism, stretching, and faulting (Fig. 5). The youngest phase, the 99–95.5 Myr Carmel volcanics, is the focus of this study (Figs. 2, 4; Gvirtzman et al., 1998; Segev et al., 2002; Griffin et al., 2018). Equivalent volcanism was documented across the Syrian Coastal Range (Ghanem and Kuss, 2013).

Fig. 4. (a) Stratigraphic correlation of six boreholes projected along strike. (b) The elevated Carmel structure is intruded and reinforced by volcanic units and surrounded by sagging flanks (after Derin, 2016).

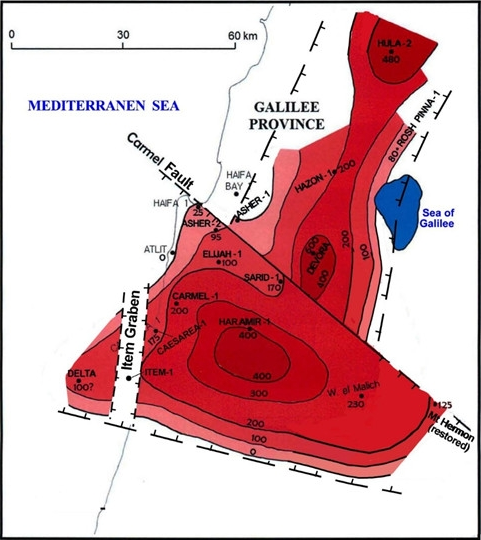

Fig. 5.Isopach of the Early Cretaceous (Berriasian) Tayasir volcanics (modified after Derin, 2016).

These Permian to Cretaceous mantle plumes drove northern Gondwana’s breakup in three stages: (1) Dextral shearing of the Tauride block opened the Phoenician basin (Schattner and Lazar, 2014) during the Permian; (2) Late Triassic to Jurassic rifting south of Carmel formed the Levant basin (Schattner and Ben-Avraham, 2007) during the second plume activity, resulting in thin continental crust or one mixed with oceanic crust; (3) Early-Late Cretaceous extension and rifting caused extensive Levant basin subsidence (Jagger et al., 2018; Segev et al., 2018). While rifting likely ceased by mid-Cretaceous (Golan et al., 2021; Sagy and Gvirtzman, 2024), the rifted margin remained elevated and near sea level until the latest Cretaceous due to prolonged Levant-Nubia plume activity (Segev and Rybakov, 2010). Recent heat flow results indicate the basin crust thinned by a factor of 2.7 since ~100 Ma, supporting the Cretaceous basin floor age (Chiozzi et al., 2023). Changes in carbonate lithofacies, from open-sea chalks to reefal limestones and dolomites, recorded environmental transitions on the water-restricted shelf during the late Albian-Turonian. Plume activities preceded the Senonian to Maastrichtian structural inversions across the Levant Basin and margin (Robertson, 2002; Segev and Rybakov, 2010).

3. Study area

The Carmel area spans 50 km × 40 km, including Mt. Carmel, Umm El Fahm, and Ramot Menashe south (Fig. 6), and contains the entire Permian to Cretaceous plume succession (Segev, 2009; Griffin et al., 2018, 2023; Golan et al., 2021). The Atlit-1 Deep well encountered 2.745 km of Cenomanian to Bajocian strata, underlain by 2.5 km of Asher volcanic and magmatic lithologies, and beneath it, 500 m of Norian volcano-sedimentary Shefayim Formation (Fig. 4; Dvorkin and Kohn, 1989; Fleischer and Varshavsky, 2002). Stratigraphic correlation indicates that the igneous complex lies atop a basement high, elevated ~1.5 km above the surrounding terrain (Derin, 2016). This complex links to a positive Bouguer gravity anomaly, indicating high-density gabbroidal bodies (Rybakov et al., 2000; Segev and Rybakov, 2010), which strengthened crustal composition in the Carmel area.

In the mid-Cretaceous, the Carmel area lay at the northwestern edge of the Arabian carbonate platform, submerged beneath a shallow inland sea (Ziegler, 2001). After Carmel volcanism ceased, the Levant margin cooled, but subsidence was delayed until the Late Maastrichtian due to regional compression (Robertson, 2002; Segev and Rybakov, 2010; Jagger et al., 2018), coinciding with a volcanic episode at 82 Ma and possibly 74 Ma (Griffin et al., 2018). After compression ended, the Carmel area subsided, reaching a depth greater than 1,000 m below sea level by the Middle–Late Eocene (Segev et al., 2011). Since the Oligocene, sub-lithospheric mantle flows from the Afar plume have triggered exhumation of the Levant margin and truncation of Late Cretaceous and younger strata (Avni et al., 2012; Wald et al., 2019). The development of the NW-trending Irbid rift during the Miocene, followed by the N-trending Dead Sea Fault system and Nile sedimentary cone accumulation, led to uplift and arching sub-parallel to the Levant margin, including ~500 m high Mt Carmel (Schattner et al., 2006; Segev and Rybakov, 2011).

4. Methods and results

The study integrates previous geological mapping, field geological mapping, borehole and geophysical data, and global seismic shear velocity data. For details, see the published study at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2025.102161.

5. Discussion

5.1 Role of volcanism

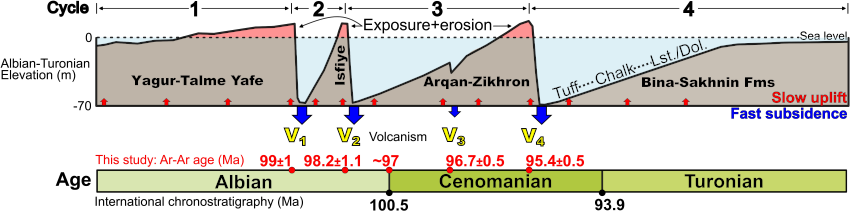

Sedimentary and volcanic characteristics observed during Cycles 1 to 4 provide evidence that shelf-edge vertical motions influenced relative sea-level fluctuations (Fig. 7). The reconstructed schematic depth curve ranges from ~70 m, as indicated by truncated pyroclastic cones, to an undetermined elevation above sea level (Sass, 1980). Between 99 Ma and 95.4 Ma, the Carmel platform developed on the rifted Levant margin bounding the young basin. At this tectonic stage, rifting significantly declined, and thermal subsidence was expected. However, the platform remained at shallow shelf depths and experienced repeated elevation fluctuations.

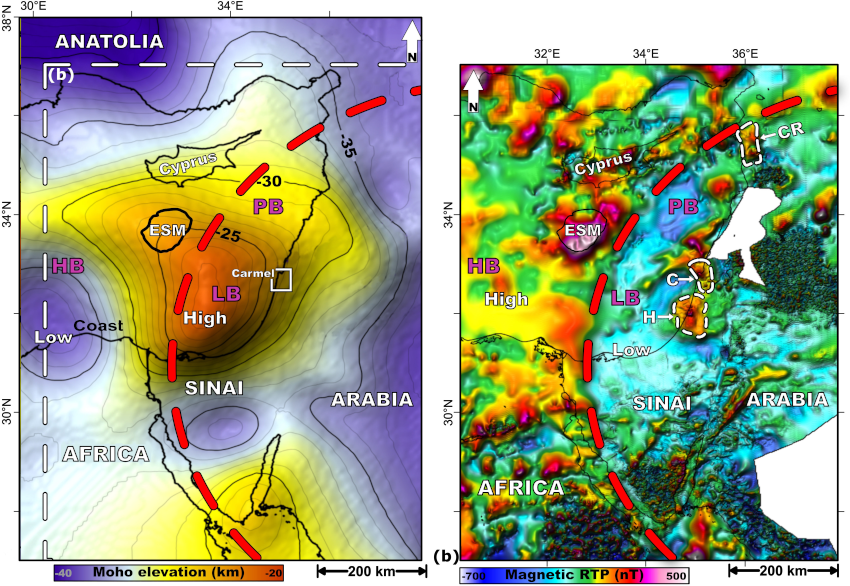

Isostatic calculations (Segev et al., 2011) indicate that plume-related magmatism maintained the platform at these elevations and produced these fluctuations (Fig. 7). This interpretation is supported by the regional Reduced to Pole (RTP) magnetic anomaly map. Predominantly negative anomalies span a ~500 km wide schematic circle, mark the Cretaceous plume-flattening zone (Fig. 8b), and a ~500 km Moho dome beneath the Levant basin and margin (Grad et al., 2009). Positive RTP anomalies in Carmel and neighboring regions imply ongoing magmatic and volcanic activity that crossed various magnetic polarities. Locally, a ~4 km² basic magmatic intrusion, detected ~0.5–1 km beneath Ramot Menashe using magnetic and gravity methods, may have increased crustal volume, resulting in differential uplift and subsidence.

Fig. 6.Elevation map of Carmel-Umm El Fahm study area with the locations of the Late Cretaceous Carmel Volcanic centers (V1-V5), outcrops presented in Figs. 7‒10 of the published paper. Numbers 1‒4 in yellow circles - locations of the stratigraphic columns in Fig. 11 of the published paper.

Fig. 7. Suggested elevation during the four Albian-Turonian cycles fluctuating between slow uplift caused by gradual heating and force folding, leading to exposure and erosion, volcanic eruptions, and pressure release, followed by rapid subsidence and submergence. In red – ages from Segev et al. (2002) and Segev (2009).

Fig. 8. (a) Moho elevation map (data from Grad et al., 2009) of the Eastern Mediterranean. The dashed white line marks the location of (b). ESM- Eratosthenes Sea Mount. (b) Regional Reduced-to-Pole magnetic anomaly map (after Segev and Rybakov, 2011). The dashed red circle in both panels indicates the extent of the magmatic material inserted into the crust by the Cretaceous Levant-Nubia Plume head and plume flattening. CR-Syrian Coastal Range (after Ghanem and Kuss, 2013); C-Carmel; H-Helez; HB, LB and PB – Herodotus, Levant and Phoenician basins.

The mainly explosive volcanism and recurring elevation fluctuations suggest temporary pressure build-up from gas accumulation and subsequent release. Gas release explains the rapid subsidence preceding tuff deposits above erosional unconformities (Fig. 7). The gas pressure likely resulted from effective decarbonation caused by magma interacting with the kilometer-thick carbonate platform (Lee et al., 2013) and by phreatomagmatic processes in shallow-marine environments. We propose that prolonged (1–3 Myr) magmatic intrusions, alongside magmatically driven decarbonation of platform carbonates and temporary gas (CO2+H2O) accumulation, drove the repeated uplift-subsidence cycles, counteracting expected thermal subsidence.

Farther north, the Aptian-Turonian Syrian Coastal Range succession shares stratigraphic and volcanic characteristics with Carmel (Ghanem and Kuss, 2013). This section includes a carbonate platform formed in a shallow continental shelf environment with repeated sea-level fluctuations and similar magmatic timing (including Albian volcanism; Mouty, 2014), supporting a common tectono-magmatic cause rather than regional tectonics controlling vertical movements during the mid-Cretaceous.

The shift to tectonic convergence with Eurasia in the Late Turonian initiated NW–SE compression and structural inversions across the Levant, forming the Syrian Arc fold belt (Hardy et al., 2010). These conditions maintained the Levant margin at shallow-water depths, without volcanism or vertical fluctuations from earlier cycles. Subsurface magmatic activity likely decreased but did not entirely cease. Regional compression may have suppressed surface ascent for 13 Myr until limited activity produced V5 at 82 Ma and possibly 74 Ma (Fig. 4; Griffin et al., 2018), facilitated by regional stretching from eastward subduction below the Eratosthenes arc (Segev et al., 2018). Following this phase, compressional forces dominated until tectono-magmatic quiescence prevailed across the Middle East from the Late Maastrichtian to Middle-Late Eocene (70–45 Ma). During this period, the Levant margin cooled and subsided until the northwestern Arabian plate became a moderately inclined ramp (Segev et al., 2011). No volcanic activity occurred after V5 until the emergence of Miocene systems from a different tectono-magmatic system.

5.2 Carmel – a long-standing elevated tectonic block

What has maintained the Carmel area as a nearly autonomous structural unit throughout its evolution? The answer likely involves magmatic reinforcement combined with bounding faults.

The extensive Permo-Triassic magmatic activity (285–240 Ma) intruded the Carmel-Helez structure (Griffin et al., 2018, 2023; Segev et al., 2018), forming a magmatic plumbing system (e.g., Magee et al., 2018) and erupting at the surface of the Helez High. Over time, intrusions cooled, lithified, and mechanically reinforced the subsurface structure of the entire high, including Carmel. During Triassic-Jurassic plume activity, extension and subsidence developed in basins east and west of the Carmel-Heletz high, with greater subsidence in the Levant basin (Derin, 2016). In the Carmel area, intense Asher volcanism began around 215 Ma and peaked between 207–201 Ma (Griffin et al., 2018; Golan et al., 2021), followed by magmatic intrusions that further strengthened the structure. The heating caused the Carmel-Heletz structure to rise into an elongated swell, while neighboring basins subsided (Fig. 4). During quiescence and cooling, the strengthened swell subsided slightly, while the stretched, thinned basins along its eastern and western flanks subsided more and accumulated greater sediment thicknesses. A swell of comparable size uplifted the ~36 km thick Negev continental crust in southern Israel during the same period (Fig. 2; Gvirtzman and Garfunkel, 1997; Gvirtzman et al., 1998).

Similar processes occurred during Cretaceous Levant-Nubia Plume activity. The vertical fluctuations reported here (Fig. 7) were recorded only in the Carmel area, with volcano-stratigraphic similarities to the Syrian Coastal Range, but were not reported from nearby regions such as the Galilee, Samaria, and Levant basin (Fig. 2). This suggests that within the dynamic updoming context, the Carmel area functioned as a fault-bounded block isolated from surrounding tectono-magmatic structures. The reactivation of these faults in later periods further isolated Carmel from Cenozoic structures developed in its vicinity on land and in the basin (Schattner et al., 2006; Wald et al., 2019).

6. Conclusions

By integrating geological data from mapping, stratigraphy, geochronology, and deep wells with geophysical gravity and magnetic methods, this study shows that the Carmel area is a long-lived (~250 Myr) structural high, reinforced by Permo-Triassic to Cretaceous magmatic intrusions. The recurring volcanism, vertical fluctuations, and volcano-sedimentary cycles (V1–V4; 99–95.5 Ma) reveal the influence of a decaying mantle plume on the evolution of the Levant continental margin. These cycles record transitions between shallow marine carbonate shelves, subaerial exposure, and explosive pyroclastic volcanism. Each cycle is characterized by rapid subsidence and chalk accumulation, followed by the development of restricted marine environments conducive to rudist reef formation and dolomitization, culminating in uplift, erosion, and renewed volcanism. The dolomite lithofacies, produced through both primary precipitation and diagenetic replacement, reflect the interplay between magmatically driven geothermal gradients, fluid circulation, and restricted seawater conditions. The cessation of volcanism after V4 and the subsequent 13 Myr gap before the final volcanic pulse (V5 at 82 Ma) signify a critical decline in plume productivity, illustrating how a waning mantle plume can drive recurring geological processes while gradually losing its ability to affect surface dynamics.

7. References

Abbo, A., Avigad, D., Gerdes, A., 2018. The lower crust of the Northern broken edge of Gondwana: Evidence for sediment subduction and syn-Variscan anorogenic imprint from zircon U-Pb-Hf in granulite xenoliths. Gondwana Res. 64, 84–96.

Al-Hadidy, A.H., 2007. Paleozoic stratigraphic lexicon and hydrocarbon habitat of Iraq. GeoArabia 12(1), 63-130.

Aqrawi, A.A., 1998. Paleozoic stratigraphy and petroleum systems of the western and southwestern deserts of Iraq. GeoArabia 3(2), 229-248.

Avigad, D., Abbo, A., Gerdes, A., Morag, N., Vainer, S., 2016. Cadomian (ca. 550 Ma) magmatic and thermal imprint on the North Arabian-Nubian Shield (south and central Israel): New age and isotopic constraints. Precambrian Res 289, 115–131.

Avni, Y., Segev, A., Ginat, H., 2012. Oligocene regional denudation of the northern Afar dome: Pre-and syn-breakup stages of the Afro-Arabian plate. Bulletin 124 (11–12), 1871–1897.

Ben-Gai, Y., Ben-Avraham, Z., 1995. Tectonic processes in offshore northern Israel and the evolution of the Carmel structure. Marine Petrol. Geol. 12, 533–548.

Best, J.A., Barazangi, M., Al-Saad, D., Sawaf, T., Gebran, A., 1993. Continental margin evolution of the northern Arabian platform in Syria. AAPG Bull. 77(2), 173-193.

Bouysse, P., Ségoufin, J., 2009. Geological Map of the World at 1:50 M (3rd ed.). Commission for the Geological Map of the World, 2 sheets.

Brew, G., Litak, R., Barazangi, M., 1999. Tectonic evolution of northern Syria: Regional implications and hydrocarbon prospects. GeoArabia 4(3), 289–318.

Chiozzi, P., El Jbeily, E., Ivaldi, R., Verdoya, M., 2023. Terrestrial heat flow and subsidence of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Tectonophysics 868, 230093.

Clift, P.D., 2005. Sedimentary evidence for mantle plume uplift in the Arabian Peninsula. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 237(3-4), 624-632.

Courtillot, V., Renne, P.R., 2003. On the ages of flood basalt events. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 335(1), 113-140.

Criniti, S., Martín-Martín, M., Hlila, R., Maaté, A., Maaté, S., 2024. Detrital signatures of the Ghomaride Culm cycle (Rif Cordillera, N Morocco): New constraints for the northern Gondwana plate tectonics. Marine Petrol. Geol. 165,106861.

Derin, B., 2016. The subsurface geology of Israel, Upper Paleozoic to Upper Cretaceous. Geological Survey of Israel, 332 p.

EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium,2025. EMODnet Digital Bathymetry (DTM 2025) EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium.

Dvorkin, A., Kohn, B.P., 1989. The Asher volcanics, northern Israel: Petrography, mineralogy, and alteration. Israel J. Earth-Sci. 38 (2–4), 105–123.

Faqira, M., Rademakers, M., Afifi, A.M., 2009. New insights into the Hercynian Orogeny, and their implications for the Paleozoic Hydrocarbon System in the Arabian Plate. GeoArabia 14(3), 199-228.

Fleischer, L., Varshavsky, A., 2002. A lithostratigraphic database of oil and gas wells drilled in Israel. Ministry of National Infrastructures, Oil and Gas Unit Rep. OG/9/02, Geophys. Inst. Isr. Rep. 874/202/02, p. 280.

Frizon de Lamotte, D., Raulin, C., Mouchot, N., Wrobel‐Daveau, J.C., Blanpied, C., Ringenbach, J.C., 2011. The southernmost margin of the Tethys realm during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic: Initial geometry and timing of the inversion processes. Tectonics 30(3), 25-46.

Ghanem, H., Kuss, J., 2013. Stratigraphic control of the Aptian-early Turonian sequences of the Levant platform, Coastal Range, northwest Syria. GeoArabia 18(4), 85-132.

Golan, T., Katzir, Y., Coble, M.A., 2018. Early Carboniferous anorogenic magmatism in the Levant: implications for rifting in northern Gondwana. Int. Geol. Review 60(1), 101-108.

Golan, T., Katzir, Y., Coble, M.A., 2021. The timing of rifting events in the easternmost Mediterranean: U-Pb dating of zircons from volcanic rocks in the Levant margin. Int. Geol. Rev. 64 (12), 1698 – 1718.

Grad, M., Tiira, T., ESC Working Group, 2009. The Moho depth map of the European Plate. Geophys. J. Int. 176, 279-292.

Griffin, W.L., Bindi, L., Cámara, F., Ma, C., Gain, S.E.M., Saunders, M., Alard, O., Huang, J.X., Shaw, J., Meredith, C., Toledo, V., 2023. Interactions of magmas and highly reduced fluids during intraplate volcanism, Mt Carmel, Israel: Implications for mantle redox states and global carbon cycles. Gondwana Res. 128, 14–54.

Griffin, W.L., Gain, S.E.M., Huang, J.-X., Belousova, E.A., Toledo, V., O’Reilly, S.Y., 2018. Permian to Quaternary magmatism beneath the Mt Carmel area, Israel: Zircons from volcanic rocks and associated alluvial deposits. Lithos 314–315, 307–322.

Guerrera, F., Martín-Martín, M., Tramontana, M., 2021. Evolutionary geological models of the central-western peri-Mediterranean chains: a review. Int. Geol. Rev. 63(1), 65-86.

Gvirtzman, Z., Garfunkel, Z., Gvirtzman, G., 1998. Birth and decay of an intracontinental magmatic swell: Early Cretaceous tectonics of southern Israel. Tectonics 17 (3), 441–457.

Gvirtzman, G., Weissbrod, T., 1984. The Hercynian geanticline of Helez and the Late Palaeozoic history of the Levant. Geol. Soc. London Special Public. 17(1), 177-186.

Gvirtzman, Z., Garfunkel, Z., 1997. Vertical movements following intracontinental magmatism: an example from southern Israel. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 102(B2), 2645-2658.

Gvirtzman, Z., Garfunkel, Z., Gvirtzman, G., 1998. Birth and decay of an intracontinental magmatic swell: Early Cretaceous tectonics of southern Israel. Tectonics 17(3), 441-457.

Hardy, C., Homberg, C., Eyal, Y., Barrier, É., Müller, C., 2010. Tectonic evolution of the southern Levant margin since Mesozoic. Tectonophysics 494(3-4), 211-225.

Hosseini, K., Sigloch, K., Tsekhmistrenko, M., Zaheri, A., Nissen-Meyer, T., Igel, H., 2020. Global mantle structure from multifrequency tomography using P, PP and P-diffracted waves. Geophys. J. Int. 220, 96–141.

Jagger, L.J., Bevan, T.G., McClay, K.R., 2018. Tectono-stratigraphic evolution of the SE Mediterranean passive margin, offshore Egypt and Libya. Geol. Soc. London Spe. Publ. 475 (1), 25–53.

Jerram, D.A., Widdowson, M., 2005. The anatomy of Continental Flood Basalt Provinces: geological constraints on the processes and products of flood volcanism. Lithos 79 (3–4), 385–405.

Kohn, B.P., Eyal, M., Feinstein, S., 1992. A major Late Devonian-Early Carboniferous (Hercynian) thermotectonic event at the NW margin of the Arabian-Nubian shield: Evidence from zircon fission track dating. Tectonics 11, 1018–1027.

Konert, G., Afifi, A.M., Al-Hajri, S., Droste, H., 2001. Paleozoic stratigraphy and hydrocarbon habitat of the Arabian Plate. GeoArabia 6(3), 407-442.

Koppers, A.A., Becker, T.W., Jackson, M.G., Konrad, K., Müller, R.D., Romanowicz, B., Steinberger, B., Whittaker, J.M., 2021. Mantle plumes and their role in Earth processes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2 (6), 382–401.

Korngreen, D., Benjamini, C., 2013. Stratigraphic evidence for shear in structural development of the Triassic Levant margin: New borehole data on the epicontinental to deep marine transition in Israel. Tectonophysics 591, 3–15.

Lang, B., Steinitz, G., 1989. K-Ar dating of Mesozoic magmatics in Israel: A review. Isr. J. Earth Sci. 38, 89–103.

Lee, C.T.A., Shen, B., Slotnick, B.S., Liao, K., Dickens, G.R., Yokoyama, Y., Lenardic, A., Dasgupta, R., Jellinek, M., Lackey, J.S., Schneider, T., Tice, M.M., 2013. Continental arc–island arc fluctuations, growth of crustal carbonates, and long-term climate change. Geosphere 9(1), 21–36.

Lu, C., Grand, S.P., Lai, H., Garnero, E.J., 2019. TX2019slab: A new P and S tomography model incorporating subducting slabs. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124(11), 11549-11567.

Magee, C., Stevenson, C.T., Ebmeier, S.K., Keir, D., Hammond, J.O., Gottsmann, J.H., Whaler, K.A., Schofield, N., Jackson, C.A., Petronis, M.S., O’driscoll, B., 2018. Magma plumbing systems: a geophysical perspective. J. Petrol. 59(6), 1217-1251.

Matthews, K.J., Maloney, K.T., Zahirovic, S., Williams, S.E., Seton, M., Müller, R.D., 2016. Global plate boundary evolution and kinematics since the late Paleozoic. Global Planet. Change 146, 226-250.

Mittlefehldt, D.W. and Slager, Y., 1986. Petrology of the basalts and gabbros from the Zemah-1 drill hole, Jordan Rift Valley. Israel Journal of Earth-Sciences, 35(1), pp.10-22.

Mohammad, S.A.G., 2006. Megaseismic section across the northeastern slope of the Arabian Plate, Iraq. GeoArabia 11(4), 77-90.

Orellana‐Rovirosa, F., Richards, M., 2018. Emergence/subsidence histories along the Carnegie and Cocos Ridges and their bearing upon biological speciation in the Galápagos. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19(11), 4099-4129.

Prokoph, A., El Bilali, H., Ernst, R., 2013. Periodicities in the emplacement of large igneous provinces through the Phanerozoic: Relations to ocean chemistry and marine biodiversity evolution. Geosci. Front. 4(3), 263-276.

Rampino, M.R., Prokoph, A., 2013. Are mantle plumes periodic?. Eos Transact. Am. Geophys. Union 94(12), 113-114.

Ribe, N.M., Christensen, U.R., 1994. Three-dimensional modeling of plume–lithosphere interaction. J. Geophys. Res. 99 B1, 669–682.

Robertson, A.H.F., 2002. Overview of the easternmost Mediterranean region: its tectonic development and significance for the oil industry. Geol. Soc. London Special Public. 207, 9-36.

Rybakov, M., Al-Zoubi, A.S., 2005. Bouguer gravity map of the Levant—a new compilation. In: Hall, J.K., Krasheninnikov, V.A., Hirsch, F., Benjamini, Ch., Flexer, A. (Eds.), Geological Framework of the Levant, Volume II: The Levantine Basin and Israel. Historical Productions-Hall, Jerusalem, Chapter 19, pp. 539–542.

Rybakov, M., Goldshmidt, V., Fleischer, L., Ben-Gai, Y., 2000. 3-D gravity and magnetic interpretation for the Haifa Bay area Israel. J. Appl. Geophys. 44, 353–367.

Sagy, Y., Gvirtzman, Z., 2024. Interplay between early rifting, later folding, and sedimentary filling of a long-lived Tethys remnant: The Levant Basin. Earth-Sci. Rev. 252, 104768.

Sass, E., 1980. Late Cretaceous volcanism in Mount Carmel, Israel. Israel J. Earth Sci. 29, 8-24.

Sass, E., Dekel, A., Sneh, A. 2013. Geological map of Israel, 1:50,000 - Sheet 5-II. Geological Survey of Israel Map.

Schattner, U., Ben-Avraham, Z., 2007. Transform margin of the northern Levant, eastern Mediterranean: From formation to reactivation. Tectonics 26, TC5020.

Schattner, U., Ben-Avraham, Z., Lazar, M., 2014. The structure of the Levant continental margin: New insights from geophysical data. Tectonophysics 617, 78–92.

Schattner, U., Ben-Avraham, Z., Lazar, M., Hübscher, C., 2006. Tectonic isolation of the Levant basin offshore Galilee-Lebanon — effects of the Dead Sea fault plate boundary on the Levant continental margin, eastern Mediterranean. J. Struct. Geol. 28, 2049–2066.

Segev, A., 2000. Synchronous magmatic cycles during the fragmentation of Gondwana: radiometric ages from the Levant and other provinces. Tectonophysics 325, 257–277.

Segev, A., 2009. 40Ar/39Ar and K–Ar geochronology of Berriasian–Hauterivian and Cenomanian tectono-magmatic events in northern Israel: implications for regional stratigraphy. Cretaceous Res. 30, 810–828.

Segev, A., Eshet, Y., 2003. Significance of Rb/Sr age of Early Permian volcanics, Helez Deep 1A borehole, central Israel. Africa Geosci. Rev. 10 (4), 333–345.

Segev, A., Rybakov, M., 2010. Effects of Cretaceous plume and convergence, and Early Tertiary tectono-magmatic quiescence on the central and southern Levant continental margin. J. Geol. Soc. London 167, 731–749.

Segev, A., Rybakov, M., 2011. History of faulting and magmatism in the Galilee (Israel) and across the Levant continental margin inferred from potential field data. J. Geodynam. 51, 264–284.

Segev, A., Sass, E., 2009. The geology of the Carmel region – report and 1:50,000 map, Atlit Sheet 3-III. Israel Geological Survey Report, GSI/7/2009, p.77 (in Hebrew with English abstract).

Segev, A., Sass, E., 2014. Geology of Mount Carmel – Completion of the Haifa region. Israel Geological Survey Report, GSI/18/2014, p. 51 (in Hebrew with English abstract).

Segev, A., Sass, E., Ron, H., Lang, B., Kolodny, Y., McWilliams, M., 2002. Stratigraphic, geochronologic and paleomagnetic constraints on late Cretaceous volcanism in northern Israel. Israel J. Earth Sci. 51, 297-309.

Segev, A., Sass, E., Schattner, U., 2018. Age and structure of the Levant basin, Eastern Mediterranean. Earth-Sci. Rev.182, 233-250.

Segev, A., Schattner, U., Lyakhovsky, V., 2011. Middle-Late Eocene structure of the southern Levant continental margin - tectonic motion versus global sea-level change. Tectonophysics 499 (1-4), 165-177.

Sleep, N.H., Windley, B.F., 1982. Archean plate tectonics: constraints and inferences. J. Geol. 90 (4), 363–379.

Steinitz, G., Bartov, Y., Eyal, M. 1992. K-Ar and Ar-Ar dating of Permo-Triassic magmatism in: Sinai and Israel - initial results. Israel Geological Society Annual Meeting, 147-148 (Abstract).

Stern, R.J., Avigad, D., Beyth, M., Miller, N., 2014. Early Carboniferous (∼357 Ma) crust beneath northern Arabia: Constraints from the Permian Al Khlata Formation, Oman. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 401, 61–70.

Torsvik, T.H., Burke, K., Steinberger, B., Webb, S.J., Ashwal, L.D., 2010. Diamonds sampled by plumes from the core–mantle boundary. Nature 466 (7304), 352–355.

Wald, R., Segev, A., Ben-Avraham, Z., Schattner, U., 2019. Tethys Ocean withdrawal and continental peneplanation — An example from the Galilee, northwestern Arabia. J. Geodynam. 130, 22-40.

Watts, A.B., Zhong, S., 2000. Observations of flexure and the rheology of oceanic lithosphere. Geophys. J. Int. 142(3), 855-875.

Weissbrod, T. 2005. The Paleozoic in Israel and environs. In: Hall J.K., Krasheninnikov V.A., Hirsch F., Benjamini C., Flexer, A. (Eds.), Geological framework of the Levant II: Levantine Basin and Israel, 283-316. Jerusalem: Historical Productions-Hall.

Wilson, M., Guiraud, R., Moreau, C., Bellion, Y.C., 1998. Late Permian to recent magmatic activity on the African-Arabian margin of Tethys. Geol. Soc. London Special Publ. 132(1), 231-263.

Wood, B.G., 2015. Rethinking post-Hercynian basin development: Eastern Mediterranean region. GeoArabia 20(3), 175-224.

Ziegler, M.A., 2001. Late Permian to Holocene paleofacies evolution of the Arabian Plate and its hydrocarbon occurrences. GeoArabia 6(3), 445-504.